Anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) surgery is the most appropriate long-term treatment for some ACL tears that are not expected to heal on their own.

The main goal of the surgery is to restore stability to the injured knee.

In This Article:

Deciding to Have ACL Surgery

Whether or not a doctor recommends surgery to repair a torn ACL depends on many factors, such as:

- Age. While there is no age cut-off for surgical intervention, it is rarely performed on individuals over age 55.

- Activity level. Surgical reconstruction may also benefit young people and those who participate in occupations or sports that involve jumping, pivoting, cutting, or rapid deceleration.

- Associated injuries. Patients with multiple knee injuries (ACL plus meniscus, fracture, or medial collateral ligament) generally benefit from surgery to prevent significant activity restrictions and minimize the risk of developing knee osteoarthritis.

An ACL tear increases the risk of developing knee osteoarthritis. Some people opt to have surgery hoping to reduce this risk. However, the effect of surgery on the development of knee osteoarthritis remains unclear.1Paschos NK. Anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction and knee osteoarthritis. World J Orthop. 2017;8(3):212-217. Published 2017 Mar 18. doi:10.5312/wjo.v8.i3.212.

See Knee Osteoarthritis Causes on Arthritis-health

A conversation about post-surgical expectations as well as long-term risks, such as arthritis, should occur before undergoing ACL reconstruction. Ultimately, it is up to the patient whether or not to have surgery.

ACL Reconstruction

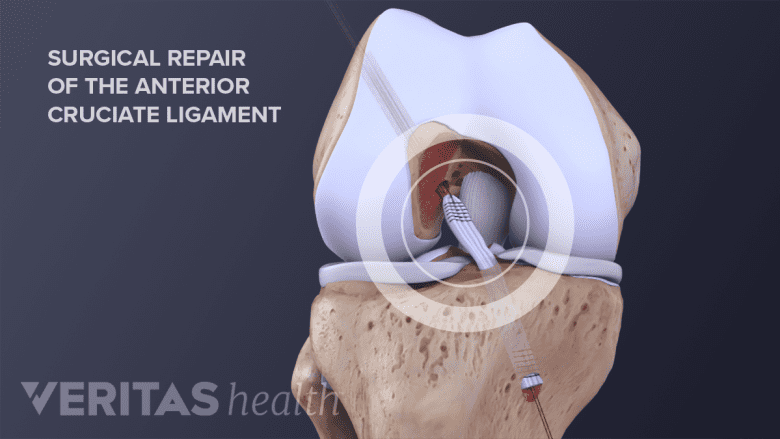

In ACL reconstruction, a graft is attached to the tibia and femur using sutures.

ACL surgery typically involves reconstructing the ligament using a graft. Reconstruction is often recommended because most injured ACLs cannot be stitched back together (repaired) due to the surrounding environment. Recent efforts have been made to find a way to improve this environment in order to repair the ACL without using a graft.2Perrone GS, Proffen BL, Kiapour AM, Sieker JT, Fleming BC, Murray MM. Bench-to-bedside: Bridge-enhanced anterior cruciate ligament repair. J Orthop Res. 2017 Dec;35(12):2606-2612. doi: 10.1002/jor.23632. Epub 2017 Jul 9. Review. PubMed PMID: 28608618; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC5729057. The graft may be from:

- The person’s own body (autograft)

- A donor (allograft)

Researchers have experimented with synthetic grafts, but so far these have proven inferior to natural grafts.3Marieswaran M, Jain I, Garg B, Sharma V, Kalyanasundaram D. A Review on Biomechanics of Anterior Cruciate Ligament and Materials for Reconstruction. Appl Bionics Biomech. 2018;2018:4657824. Published 2018 May 13. doi:10.1155/2018/4657824.

Below are the most common tissues used for ACL grafts. The graft material acts as a scaffolding for new ligament tissue to grow on.4American Academy of Orthopeadic Surgerons website, Ortho Info. Anterior Cruciate Ligament (ACL) Injuries. Accessed April 8 2019. Each type of graft material offers unique benefits.

- Patellar tendon. A patellar tendon autograft utilizes the patient’s own tendon to replace the torn ACL. The patellar tendon is known to heal quickly, which makes it a popular choice for a graft.

- Hamstring tendon. Autografts using the patient’s hamstring have become increasingly more common. They have shown decreased post-operative knee pain and easier surgical recovery compared to patellar tendon grafts.4American Academy of Orthopeadic Surgerons website, Ortho Info. Anterior Cruciate Ligament (ACL) Injuries. Accessed April 8 2019.

- Quadriceps tendon. Quadriceps autografts are often used on people who have previously had ACL reconstruction.

- Cadaver tendon. Allografts, which are the utilization of cadaver tendons, are preferred by some surgeons because they do not require removal of the patient’s own tendon.

No specific graft type has proven to be superior aside from that with which a particular surgeon is most experienced.

ACL reconstruction is typically done using a minimally invasive, arthroscopic approach. Special surgical tools and a video camera are inserted through small incisions in the knee joint. The surgeon will secure the graft to the tibia (shin bone) and femur (thighbone) using sutures (special surgical thread).

ACL Surgery Recovery

Generally, ACL surgery does not require an overnight stay in the hospital. Most people can move the knee immediately following surgery. Within a few days, post-operative rehabilitation may begin. Rehabilitation is essential to:

- Maximizing long-term outcomes

- Improving range of motion

- Increasing strength

- Restoring balance and proprioception

See Advanced Exercises to Restore Proprioception

Formal physical therapy is often recommended after surgery. Some surgeons recommend the use of knee braces; however, there is no evidence demonstrating improved outcomes with their use.5Mayr HO, Stüeken P, Münch EO, Wolter M, Bernstein A, Suedkamp NP, Stoehr A. Brace or no-brace after ACL graft? Four-year results of a prospective clinical trial. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2014 May;22(5):1156-62. doi: 10.1007/s00167-013-2564-2. Epub 2013 Jun 27. PubMed PMID: 23807029.

Some research indicates that it may take more than 6 months to regain symmetrical knee functionality.6Cristiani R, Mikkelsen C, Forssblad M, Engström B, Stålman A. Only one patient out of five achieves symmetrical knee function 6 months after primary anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2019 Feb 18. doi: 10.1007/s00167-019-05396-4. [Epub ahead of print] PubMed PMID: 30778627. In general, an athlete can return to his or her sport between 9 and 12 months following surgery. The orthopedic surgeon will determine when it is safe to return to athletic activities.

- 1 Paschos NK. Anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction and knee osteoarthritis. World J Orthop. 2017;8(3):212-217. Published 2017 Mar 18. doi:10.5312/wjo.v8.i3.212.

- 2 Perrone GS, Proffen BL, Kiapour AM, Sieker JT, Fleming BC, Murray MM. Bench-to-bedside: Bridge-enhanced anterior cruciate ligament repair. J Orthop Res. 2017 Dec;35(12):2606-2612. doi: 10.1002/jor.23632. Epub 2017 Jul 9. Review. PubMed PMID: 28608618; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC5729057.

- 3 Marieswaran M, Jain I, Garg B, Sharma V, Kalyanasundaram D. A Review on Biomechanics of Anterior Cruciate Ligament and Materials for Reconstruction. Appl Bionics Biomech. 2018;2018:4657824. Published 2018 May 13. doi:10.1155/2018/4657824.

- 4 American Academy of Orthopeadic Surgerons website, Ortho Info. Anterior Cruciate Ligament (ACL) Injuries. Accessed April 8 2019.

- 5 Mayr HO, Stüeken P, Münch EO, Wolter M, Bernstein A, Suedkamp NP, Stoehr A. Brace or no-brace after ACL graft? Four-year results of a prospective clinical trial. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2014 May;22(5):1156-62. doi: 10.1007/s00167-013-2564-2. Epub 2013 Jun 27. PubMed PMID: 23807029.

- 6 Cristiani R, Mikkelsen C, Forssblad M, Engström B, Stålman A. Only one patient out of five achieves symmetrical knee function 6 months after primary anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2019 Feb 18. doi: 10.1007/s00167-019-05396-4. [Epub ahead of print] PubMed PMID: 30778627.