The hip joint serves as the central link between the upper body and the legs and is one of the largest weight-bearing joints.

The hip’s unique anatomy anchors the body's weight, facilitates balanced movement, and provides stability in every step.

The hip joints connect the pelvis to the thigh and enable movements such as walking, running, sitting, and standing.

The term “hip” is used in various contexts:

- Hip joint. Medically, the term "hip" refers to the joint connecting the pelvis and the thigh.

- Pelvic bone. Colloquially, “hip” typically refers to the butterfly-shaped pelvic bone (pelvis).

This guide provides a complete visual medical explanation of hip joint anatomy and function, including how the hip joint seamlessly interacts with its surrounding tissues.

In This Article:

- Your Visual Guide to Hip Anatomy

- Hip Bone Anatomy

- Hip Muscle, Tendon, and Ligament Anatomy

Hip Joint Anatomy

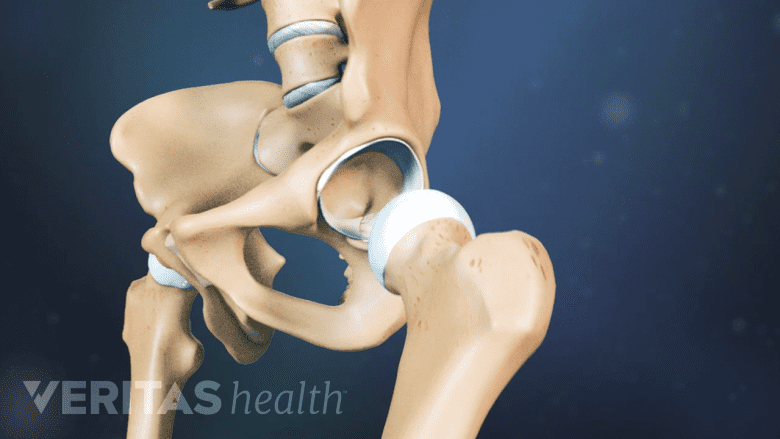

The hip joint is made up of a ball (upper end of the thighbone) and socket (depression in the pelvis).

The hip joint is a ball-and-socket joint formed by the joining of 2 bones – the “ball” is the knobby head of the thighbone, or femur, that fits into the “socket” – a shallow cup-shaped depression in the pelvis called the acetabulum.

The hip is the body’s largest ball and socket joint, and the shoulder is the second largest.

The hip joint is described by its anatomical features and location.

- There are two hip joints – one on each side of the pelvis, located slightly above the “sit bones” (ischial tuberosities) at the base of the pelvis.

- The hip is classified as a synovial joint – a type of joint where the bones are lubricated, freely mobile, and enclosed within a fibrous capsule filled with synovial fluid.

- The joint is protected by the upper rounded crest of the pelvic bone (iliac crest), the bony protruding bump on the side of the thighbone (greater trochanter) and several layers of muscles and soft tissues. The iliac crest and greater trochanter also serve as attachment points for the muscles that control hip motion.

- The hip is a deep joint and cannot be felt directly by touching or pressing near its location.

- The hip is also referred to as the:

- Acetabulofemoral joint, because it connects the acetabulum (“acetabulo”) to the femur (“femoral”). This is the most commonly used term to describe the joint.

- Coxofemoral joint, because it connects the pelvic bone (ox coxae) to the femur (“femoral”)

Due to its weight-bearing function and structure as a ball and socket joint, the hip is prone to injuries from daily activities, contact sports, accidents, tripping, falls, and overuse injuries.

Hip Joint Functions

The primary functions of the hip include:

- Provide balance and support for the upper body

- Move the thigh and leg in several directions

- Absorb shock transmitted from the upper body to the legs and from the legs to the upper body

The hip’s ability to balance forces through its full range of motion provides stability for everyday activities, such as standing, running, maintaining a steady and balanced gait, sitting on or rising from a chair, lifting weight from a squatting position, bending forward at the waist, and bending the knee to climb stairs.

6 Types of Motion at the Hip

The hip’s spheroidal ball-and-socket construction allows for 6 distinct types of movements in a range of directions:

- Flexion – moving the leg forward, such as when taking a step, lifting the knee upward toward the chest, bending down, or squatting

- Extension – moving the leg back, such as when walking backward

- Abduction – moving the leg out to the side, such as while getting in or out of a car or stepping to the side

- Adduction – moving one leg toward the other leg, such as while crossing the legs

- Internal rotation – turning the thigh toward the midline of the body, such as the twisting movement of a baseball batter’s front leg when about to hit a ball

- External rotation – turning the thigh out away from the midline of the body, such as a ballet dancer turning their legs outward for various dance positions.

The most common daily hip movements include flexion, extension, and abduction involved in walking.

See 3 Simple Stretches for Hip Pain Relief

The hip’s maximum range of motion occurs during flexion, and the least movement occurs during extension.

Hip Joint Blood Supply

The hip joint receives blood from several sources, ensuring adequate oxygenation and nutrient delivery to its structures.

The primary blood vessels supplying the hip include branches of the following arteries:

- Medial circumflex femoral artery (blood supply to the hip joint)

- Lateral circumflex femoral artery (blood supply to the hip joint)

- Superior gluteal artery (blood supply to the buttock and thigh region)

- Inferior gluteal artery (blood supply to the buttock and thigh region)

A severe injury to the hip, such as hip dislocation or fracture, can damage these blood vessels, causing bleeding, blood clots, or inflammation of the blood vessels.

In rare cases, problems with the hip’s blood supply cause serious conditions such as:

- Deep vein thrombosis – blood clots in the deep vein(s) of the leg.

Deep vein thrombosis is a common complication of total hip replacement surgery and total knee replacement surgery. - Avascular necrosis or osteonecrosis – the death of hip bone tissue due to a lack of blood supply.

- Legg-Calvé-Perthes disease – a childhood condition where the blood supply to the femoral head is interrupted, causing bone death.

Early medical treatment is warranted in these conditions.

Hip Nerve Supply

Nerves descending from spinal nerve roots L1 to L4 innervate the hip joint.

Innervation of the hip joint is provided by nerves originating from the spinal nerve roots L1 to L4 and include the:

- Femoral nerve

- Obturator nerve

- Sciatic nerve

In addition to transmitting nerve signals from the brain to control hip movement, these nerves also transmit sensory information from the hip joint to the brain, allowing for proprioception (awareness of joint position) and pain perception.

Impaired nerve function leads to reduced healing, decreased joint stability, and increased susceptibility to injury and degenerative changes.

Soft Tissues of the Hip

The hip joint is held together by an extensive architecture of soft tissues – muscles, tendons, and ligaments – permitting stable yet flexible support to the upper body and motion for the lower body.

Two spongy fluid-filled sacs called the trochanteric bursa and the iliopsoas bursa are located between the hip’s bones and soft tissues for cushioning and shock absorption during hip movements.

Identifying Hip Pain

Identifying the root cause of hip pain and dysfunction is often difficult due to the hip’s complex anatomy and the surrounding structures. A hip problem can cause hip pain, hip or leg weakness, or altered gait mechanics. The symptoms can be localized to the hip, groin (inner thighs), buttocks, lower back, outer part of the thigh, back of the thigh, front of the thigh, and/or the knee.

Hip pain is diagnosed and treated by doctors trained in musculoskeletal conditions, such as physiatrists, sports medicine specialists, physical therapists, chiropractors, and orthopedic surgeons.