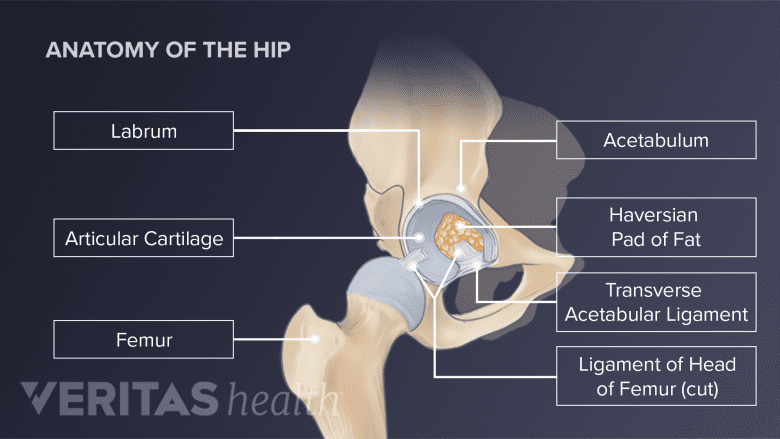

The hip joint is formed by 2 bones: the femur (thigh bone) and the acetabulum (bony socket in the pelvis). Cartilage cushions the joint's bones, while surrounding tissues and fluid keep it moving smoothly.

In This Article:

- Your Visual Guide to Hip Anatomy

- Hip Bone Anatomy

- Hip Muscle, Tendon, and Ligament Anatomy

Hip Bones

The hip is formed by the articulation between the rounded femoral head and the acetabular socket.

Essential characteristics of the bones forming the hip joint are described below:

- The femur is the longest bone in the body, extending from the hip joint to the knee. The top of the femur bone has 2 separate rounded parts:

- Femoral head. A bulbous "femoral head" connects to the pelvis and forms the “ball” of the ball-and-socket hip joint. The part immediately below the femoral head is called the femoral neck – a flattened pyramidal bone connecting the femoral head to the rest of the thigh bone.

- Greater trochanter. At the top of the femur, there is a wider and more prominent bony knob called the greater trochanter. This knob serves as an attachment point for several muscles around the hip joint. The greater trochanter is a part of the femur, but it is not a part of the hip joint.

- The acetabulum is the bony socket that holds the femoral head. This socket is formed by the fusion of 3 pelvic bones – ilium, ischium, and pubis

The acetabulum is a unique and complex structure with the following distinct characteristics:

- Femoral coverage: The acetabulum does not fully house the head of the femur – it covers about 40% of the femoral head at any given time.1Glenister R, Sharma S. Anatomy, Bony Pelvis and Lower Limb, Hip. [Updated 2023 Jul 24]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK526019/

- Femoral contact: The deepest part of the acetabulum does not contact the femur and is filled with a fatty tissue called the Haversian pad of fat.2Nelson FRT, Blauvelt CT. Anatomy and orthopaedic surgery. In: A Manual of Orthopaedic Terminology. Elsevier; 2007:191-262. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-323-04503-2.10008-8

- Superior dome: The upper front part of the acetabulum, called the superior dome, is the weight-bearing portion of the pelvic bone and the hip joint.2Nelson FRT, Blauvelt CT. Anatomy and orthopaedic surgery. In: A Manual of Orthopaedic Terminology. Elsevier; 2007:191-262. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-323-04503-2.10008-8

- Ossification and fusion: In children and young adults, some parts of the acetabulum are cartilaginous, fully developing and fusing into hard bone by the age of 20 to 25 years.1Glenister R, Sharma S. Anatomy, Bony Pelvis and Lower Limb, Hip. [Updated 2023 Jul 24]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK526019/

Conditions that involve the hip bones affect their structure, strength, and function, and include:

- Hip fracture: The femoral neck or upper part of the femur near the greater trochanter is the most common site for a hip fracture.

- Hip dislocation: A hip joint dislocation occurs when the hip’s femoral ball slips out of the acetabular socket.

- Femoroacetabular impingement (FAI): Commonly referred to as hip impingement syndrome, this condition occurs due to abnormal contact between the hip bones that causes damage to the joint.

- Hip osteoporosis: A condition characterized by weak hip bones that are susceptible to a hip fracture from a fall or other relatively minor trauma. This condition is more common in individuals of advanced age.

- Developmental dysplasia of the hip: A congenital condition where the hip socket is shallow, causing the femoral head to slip in and out of the socket.

- Slipped capital femoral epiphysis: A condition in adolescents (typically between the ages of 8–15) where a part of the femoral head slips off the acetabulum due to a defect in bone growth.

- Bone infection or osteomyelitis: Infection of the hip bones, usually caused by bacteria.

- Bone tumors: Benign or malignant growths in the hip bones, such as osteosarcoma or chondrosarcoma.

These conditions reduce the function and mobility of the hip, leading to varying degrees of pain and disability.

Hip bone anatomy differences in men and women

Women have 2 key differences in their hip bones when compared to men3Wang SC, Brede C, Lange D, et al. Gender differences in hip anatomy: possible implications for injury tolerance in frontal collisions. Annu Proc Assoc Adv Automot Med. 2004;48:287-301. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3217425/:

- A deeper acetabulum

- A smaller femoral head

This anatomical structure in women makes the femoral “ball” lodge more securely in the deeper acetabular “socket,” – creating a more stable hip joint in women, which is comparatively less prone to injury and trauma.3Wang SC, Brede C, Lange D, et al. Gender differences in hip anatomy: possible implications for injury tolerance in frontal collisions. Annu Proc Assoc Adv Automot Med. 2004;48:287-301. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3217425/

Hip Articular Cartilage

A layer of slippery, strong, and flexible cartilage covers the joint surfaces of the femur and the acetabulum and serves 2 main functions:

- Ensure smooth joint movements: When the femoral head rotates in the acetabulum, the articular cartilage allows the two surfaces to glide against each other.

- Facilitate shock absorption: Articular cartilage acts as a shock absorber, absorbing impact and preventing direct bone contact (such as while running or jumping).

The thickness of the articular cartilage varies, with thicker regions found in areas subjected to the greatest force when the hip joint is loaded.1Glenister R, Sharma S. Anatomy, Bony Pelvis and Lower Limb, Hip. [Updated 2023 Jul 24]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK526019/

When articular cartilage is damaged or wears out, it provides less protection against friction and impact, leading to conditions such as a hip labral tear and hip osteoarthritis.

Hip Capsule, Synovial Membrane, and Fluid

A fibrous, tough capsule encases the hip joint. The capsule is formed by 3 hip ligaments – the iliofemoral, pubofemoral, and ischiofemoral ligaments.1Glenister R, Sharma S. Anatomy, Bony Pelvis and Lower Limb, Hip. [Updated 2023 Jul 24]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK526019/

The inner surface of the capsule is lined by a specialized synovial membrane responsible for generating synovial fluid, a thick gel-like substance, that lubricates the joint and delivers essential nutrients.

Synovial fluid is produced when the joint is used. When the hip is at rest, the synovial fluid is absorbed in the cartilage, like water in a sponge. The synovial fluid is squeezed out when the hip moves or bears weight.

Hip Labrum

The labrum forms a seal around the acetabular socket and holds the hip joint together.

The labrum is a tough cartilaginous ring that forms a collar surrounding the acetabulum, providing stability to the hip joint.

Hip labral tissue serves to:

- Deepen the hip socket

- Provide structure for the hip joint by limiting the extreme range of motion in the joint

- Seal the joint fluid inside the joint

- Transmit loads from the upper body to the legs

The labrum extends down from the acetabulum to cover more of the femoral head – like a rubber seal – and increases the volume of the acetabulum by 33%.1

Labral tears are a common problem in the hip joint. The labrum may also fray, become inflamed, or fully detach from the acetabulum.

Labral tears may occur with or without pain and instability in the hip joint. If left untreated, a labral tear is a risk factor for developing hip osteoarthritis.

- 1 Glenister R, Sharma S. Anatomy, Bony Pelvis and Lower Limb, Hip. [Updated 2023 Jul 24]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK526019/

- 2 Nelson FRT, Blauvelt CT. Anatomy and orthopaedic surgery. In: A Manual of Orthopaedic Terminology. Elsevier; 2007:191-262. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-323-04503-2.10008-8

- 3 Wang SC, Brede C, Lange D, et al. Gender differences in hip anatomy: possible implications for injury tolerance in frontal collisions. Annu Proc Assoc Adv Automot Med. 2004;48:287-301. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3217425/